Religion is culture. Culture is religion.

Hey, I didn’t create those phrases. But they are useful ways of approaching writing about religion, and understanding religion in fiction and reality. So why does every culture seem to have its own religion? Why is English Protestantism so different from American Protestantism, why is Iraqi Sunni Islam so different from Iranian Shia Islam? Why is Kenyan Ismaili Islam so different from each?

Leaving aside the purest matters of faith and belief, and from a purely historical viewpoint, the differences are societal and cultural. As people form different cultures, they develop different spiritual needs. And viewed through the cold, unrelenting lens of anthropology (which, to be fair, has turned out to be a cold, racist lens, but there’s still merit in many of its pronouncements) the needs of a culture may begin with quaint peasant dances; eventually those dances are codified into which ones are ‘right’ and which are ‘wrong’ and then, at some point, the rightness reaches a state at which the dance is ‘sacred.’

Or, just possibly, the Imams and the grim Geneva ministers decide that all dance is profane, secular, or downright ‘sinful.’ Meaning, for example, that it allows young men and women promiscuous contact that can interfere with the orderly direction of the culture, at least as promulgated by the Imams and the ministers, all of whom, you note, are men. That’s for another blog.

It is not my intention in today’s piece to discuss the many failings of organized religion… except, in fact, to comment that most of the failings ascribed to religion are in fact biases inherent in culture. Religion is, in a way, the most codified, most rigorous form of culture (and that’s why it generates so much art), but it’s still merely a reflection of society’s needs and desires. It is human; it is about the systems that govern human animals.

What I’m interested in, and what, by extension, I rather hope all of you are interested in, is the writing of religion in historical fiction and in fantasy. So let me start with the sort of broad, sweeping statement that would annoy me in someone else’s blog.

For most of human history, people have actually believed in the divine and the supernatural.

There it is.

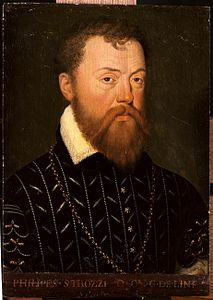

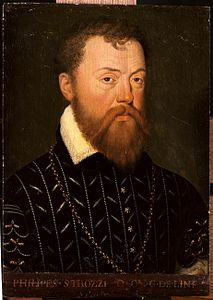

I mean, it is always possible to find atheists and near atheists, and to comfortably give them modern belief systems. Piero Strozzi comes to mind. His brother was the Prior of Capua and a Knight of Saint John, and he was once proposed to the pope as a cardinal, but he was apparently an absolute atheist, and on his death bed, when asked if he would renounce sin and acknowledge God, he said something like ‘If there is a god, which I very much doubt, he is a gentleman and will be no more impressed with my late conversion than I with his late appearance.’ For a 16th century Italian, that’s some serious atheism. He’d be an easy, modern character to write, and in fact, Dorothy Dunnett did a great deal with him and his religious, piratical brother.

Such men and women have existed in every generation. in every culture. I can catalog for you a number of major Christian thinkers who seem to have lost their faith or questioned the existence of god, especially across the Middle Ages and into the fifteenth century; I could, if I wanted to stir up controversy, name a major Islamic thinker who appears to me to have eschewed all forms of theism at the end of his life. Such men and women existed. Finding religion irrelevant and even silly or irrational was not invented in the last fifty years.

But…

Let’s have a little look at why we read historical fiction, shall we? Isn’t it to immerse ourselves in the past? Isn’t it a desire to experience, if only indirectly, the ‘other country’ that existed somewhere and to which we can otherwise never go? (And in fact, is this not the very same reason we read fantasy?). So when we give a medieval character a modern, rational-materialist ethic or morality, aren’t we kind’a cheating?

And even if that person existed, isn’t she more of an outlier? Perhaps an interesting character, but hardly a typical one. Dorothy Dunnett used Piero Strozzi for contrast. Not as a norm.

And… even more so, in a fantasy environment where the Gods are immanent? I mean… isn’t it patently silly to be an atheist when god keeps appearing at your elbow? Or dropping rocks on your army? (I will return to this thought in another blog, too).

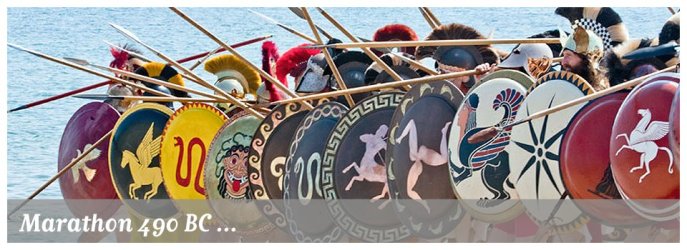

I began my writing career (leaving aside spy novels and Washington and Caesar) with the Tyrant series and Hellenistic Greece. And that immediately confronted me with a vast array of possible attitudes for my protagonists, because, in fact, the Hellenistic era was rife with both cynicism and piety. And new spirituality — the messiah, for example. (Not ‘The Messiah’ either, but a plethora of them. A trend.)

Ah, time for an excursus on piety versus faith. To me, as an historian, piety is about the rigorous practice of ritual and matters of religion; praying to Mecca, crossing oneself, bowing one’s head every time the name of Jesus is mentioned, performing one’s ritual sacrifice with precision, so that the blood flows nicely over the altar, rattling away with that prayer wheel….

This is and is not the same as faith. To me, faith is the actual feeling of belief in the divinity and/or supernatural. Each can affect the other, but they are different,and where faith can exist independently of culture (for example, a Persian in 6th c. BCE Anatolia might suddenly develop a belief that the Greek hero Herakles played a major role in saving him from disease), we usually see piety as deeply embedded in cultural practice (look at Italian Catholic ritual practice and then at French or English Catholic ritual practice, for example).

And a character in Hellenistic times might well perform multiple acts of piety, sacrificing animals for example, because of the important social issues surrounding piety. (I recently read an article that argued that Roman religion was entirely about piety; about ritual performance). In Ancient Greece, to publicly perform some rituals was to be a priest, and priests were often high ranking aristocrats, directly related to and descended from the god they worshiped. Ritual performance reinforced social status and, of course, provided proof of the performers descent from the Gods, a nice package. And by the way, when you are descended from Herakles, how exactly do you decide that you don’t believe in Herakles?

Because to disbelieve in Herakles would lead to a cascade of other collapsed beliefs. It would mean that you no longer saw yourself as descended from the gods. That might further imply that you had no particular right to rule other men or own slaves. Or fight wars of dominance. You would now have to redefine your relationship with the supernatural, with the natural order, with other men and other women. Because being descended from Herakles was at the very heart of what it meant to be YOU. And when you ‘admit’ that there is no Herakles….

You are someone else.

You are no longer the same person you were moments ago, and you are going to find this experience pretty traumatic. I have launched off on this little side-road in religion and belief mostly to remind all of you about character, motivation, and plot; and why religion plays a major role in belief and thus in motivation; how the collapse of belief would be a horrible experience, and force a massive and perhaps pernicious reshaping of character. All my rational materialist friends will now cry foul and tell me that it will lead naturally to a more honest and rigorous examination of the world, but as an historian, I’m going to say that in Hellenistic Greece and Renaissance Italy, what I see in the end of belief is a stunning void in ethics and a shocking expansion of selfishness and greed.

Modern corporatism, anyone?

And of course, when people ask questions like ‘Why does x religion believe something so stupid as y, and why don’t they just fix that’ the little historian in me comes out and says… well, it probably had an important role in culture, once, and even though that role is now lost, the belief system remains and is important to many people at an almost instinctive level. Like eating pork. Or…

closer to home… Protestant and Catholic Ireland. I’m going to say, as someone who enjoys the ‘game’ of historical theology, that most modern Irish men and women — and their North American descendants — could not tell me in ten sentences what it was in the 16th and early 17th century that separated mainstream Catholic from mainstream Protestant theology. (NB, if Martin Luther was alive today, he would be a hyper-conservative Roman Catholic.) And I’ll further posit that the great mass of those same people no longer practice EITHER form of Christianity. And yet, my experience tells me that they cling to bias about the other group. It has become cultural,. even though, in this case, it started as a philosophical/theological issue at the very most esoteric level.

I’ve probably beaten the heck out of this dead horse. But for the sake of argument, the converse is often true. So, for example, presented with an MP3 player loaded with the Latin mass of Thomas Tallis alternating with calls to prayer by an expert Muezzin, most western agnostics and atheists will nonetheless prefer the former. Aesthetically. For cultural reasons.

All the way back to my first assertion. Most people in history believed in the divine and the supernatural. To me, having posited this, it’s essential to write most characters as pious or at least ‘automatically’ or unthinkingly religious. What one does in this way, however tempered, is to provide a glimpse of the mindset of the past; to allow our reality to be filtered by their belief system so that we see, even if through a glass darkly, something of the image system of the past. With the Greeks, I spent a fair amount of time on philosophers, because my ideas about Greek religion, when they go beyond wine spilling and ritual practice, are bound up with my (modern, flawed) appreciation of the Greek philosophers. But, like transmitting my reenacting experience of armour and battle, it does help you, the reader, to ‘be’ in the past for a moment, or a set of moments, even in a flawed way.

I am asked from time to time why the world of the Red Knight novels includes Christianity (and Judaism and Islam, if you’re looking). There are two reasons. One is still my secret, and is about my ‘cosmology’ of why and what this world is. But the other is a matter of record. I’m an historian of Chivalry. I wanted my pseudo-Arthurian world to feel right and exist in the cultural world of Chivalry. It is a truism of the study of Chivalry that there is no chivalry without Christianity. It might look a little like chivalry, but it’d be something different. There is a fad to Celticize Arthur, but to do so is to ignore most of the source material and to add some (to me) unsavoury concepts. When I say ‘The Arthurian Mythos’ I mean the material of the French poets of the 13th and 14th centuries that ends up as the English ‘Morte D’Artur’ as collected by Mallory. And boy does all that material pack a Christian punch. I’d even go so far as to say that the early books in the cycle appear to be a Lay Christian attempt to write ‘Gospels’ for the Chivalric class. In effect, they were creating a new religion.

I suppose that I, too, might have created a religion. Or, in line with others, I might have merely re-written a religion that was, in effect, the same, but with different names. Certainly this has been done in the Fantasy genre, with several different religions. It seems to satisfy… but it doesn’t satisfy me. Let me just try two thoughts on you.

Case one. Casual blasphemy.

Casual blasphemy is an essential marker of military speech and has been for as far back as we have archaeology and graffiti. And who can make up a pantheon of saints and martyrs as extensive and deeply imagined as the cannon of Christian theology? Not just Christianity, either… what fantasy religion has the living, breathing sheer wonder and artistic insanity of 17th century Buddhism?

Or 14th c. Christianity, I agree. Either way, all those saints and demons give people so many different ways to swear; in belief and disbelief, in piety and in its opposite. But to read and understand blasphemy requires that you, the reader, have a deep understanding of the cultural norm, so that the nuance of the blasphemy resonates.

And (on to point two) how much exposition would it take me to tell you, the reader, about the crucified messiah who is and is not viewed as the militant sword-bearing leader of a religion that professes peace but makes war and idolizes its war-makers when they wear shiny armour? How much pointless character conversation would it take to sell you that, however internally conflicted, Bad Tom and Willful Murder and Sauce all actually believe, in their spiritual core, in the tenets of this made-up religion, and the way it interacts with their professional violence making?

Especially since this hypothetical made-up pseudo-Christian religion would never have the depth of resonance for the cult of Chivalry that the real thing did. Not to mention that King Arthur and his knights were all… part of the Christian mythos.

Poor, peace-loving Jesus.

These are deep, murky waters. Even in writing this I found I was unwilling, for example, to offend with a really solid example of blasphemy. But… I’ll close with a couple of almost unrelated thoughts. First, I’m writing the end of the Arimnestos series; pretty soon, I’ll begin writing a new fantasy series. In the new fantasy, there will be four major religions and I’ll be creating each of them… they will be original… or will they? I mean, there will be elements of religion as I understand it, created by me; but I’ll be heavily influenced by history and theology we know; Confucianism; Buddhism; Taoist belief; Islam, Animism, Zoroastrianism… and Christianity, of course.

Human beings have dealt with religion, divinity, the supernatural and the consequences of the supernatural in a great many ways. I’m not sure I’m a sufficiently original thinker to actually go very far outside that box… But whatever I create, it will be complicated, nuanced, and people will both believe in it and paradoxically, have blasphemies and indulgences.

But for the most part, they will believe. They won’t all believe the same things; like us, they’ll debate what actually happened, and some will see the divine where others see the natural.

Whatever ‘natural’ is.

The second of my three unrelated things is that I’ve been running RPGs since I was fourteen. I’m fifty-three now. That’s almost forty years of making shit up on the fly, and one of the things I was introduced to very early (my friend, the philosopher Mark Stone, is to blame) was the concepts of cosmology and ontology. Or, in brief… the big WHYs. Why is there a world? Why is there magic? Science? Gravity? Steel armour? Religion? Seriously… you only have to run a role playing campaign for about fifteen minutes without thinking any of these through, and then suddenly a player asks as question and you are left facing the abyss. I mention this because a few readers seem to imagine I’d never given thought to creating my own religions for Red Knight. Really.

And I have been graced with friends who do religion and philosophy for a living, and as a major part of their lives. My writing is heavily influenced by philosophy and philosophical issues; sometimes by theology as well. Dr. Rajiv Kaushik introduced me to Husserl and his thoughts on experience and history (which even appear in this blog) and more recently, my friend Dr. Alice McLachlan has helped me think about art and culture and politics. Not to mention various priests (Father WIlliam O’Malley SJ comes to mind, and Dr. Peter Robinson (who is an Anglican priest and family, too…) and deacons, like my friend Tom Uschold, who, to complete the circle, also marches into the field in the 18th century and the Middle Ages…

It’s not all swords and armour. If you are going to write about the past… or create a world from whole cloth… it’s essential to imagine ‘being’ in that world, in that time, in that culture, in that belief system.

Or so says I.

The last and least important comment is that I am, myself, a person of faith. To me, that’s neither here nor there. I’m not, in fact, a devotee of Herakles and Hephaestus, but Arimnestos is, and I try very hard to make him pious and also faithful. Arimnestos is in no way a Christian; merely a man of his time. That’s writing. It’s like method acting.

Gabriel Muriens has a journey in the discovery of faith or lack thereof, but again, that’s writing; in the Western tradition of literature, that’s a good, solid, mainline Epic plot.

On the other hand, and to be fair, as an Anglican with high church leanings, I adore ritual, and I suppose that helps me write about hermetical magic.

So… in the end, as a writer, what matters is that religion is culture, and culture is religion.

By the way, This is my favorite religious painting; ‘The Virgin in the Rose Garden’ in Verona, Italy. The lady at the top is the Virgin Mary, although if you look closely, you’ll see some Eastern influences. That lady at the bottom of the image is Saint Catherine. Because her wheel is lying there in the ground with a nice late 14th c. arming sword. There’s more symbolism in ‘The Virgin in the Rose Garden’ than you can shake a stick at; it’s at the crossroads of the worlds of Christianity and Chivalry, and oh, by the way, the artist was massively influenced by Iranian court painting –that’s Shia Islam; and perhaps by Buddhist painting, too. Because, always, always, its way more complicated than it looks.

Oh by the way, Tom Swan and the Last Spartans (Episode 1 of Book 3) is out today!